Education and the Politics of ‘Disadvantage’ re Gonsky

Explainer: What is a ‘Gonski’ anyway?

Author

Disclosure statement

Bronwyn Hinz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

Victoria State Governmentprovides funding as a strategic partner of The Conversation AU.

View current jobs from University of Melbourne

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

This week you might have heard the word “Gonski” even more than usual.

That’s because the Gillard government finally announced how it would pay for its school funding reform in the lead up to its meeting with the states – who it needs to help fund the changes. Yesterday the states failed to sign up to the reforms but what does that really mean?

In order to understand the significance of the reforms, based on the landmark Gonski review on school funding, you need to understand how the current system works, what’s wrong with it and what proposals there are to fix it.

The current system

Australia’s school funding arrangements are unnecessarily complex, opaque, ineffective and inequitable. It compounds disadvantage and limits the nation’s education performance.

It’s actually dozens of systems, public and private, state and commonwealth. Each of which is reformed without respect to the others, creating a veritable jungle of policies which limits accountability and contributes to growing resources and performance gaps between rich and poor schools, with disadvantaged students suffering most.

Under the Australian Constitution, schooling is a residual responsibility of the states (that means it isn’t listed as a Commonwealth power under section 51).

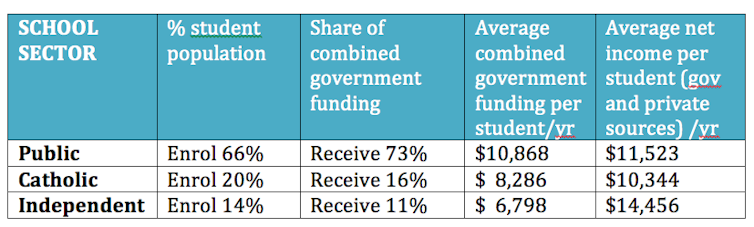

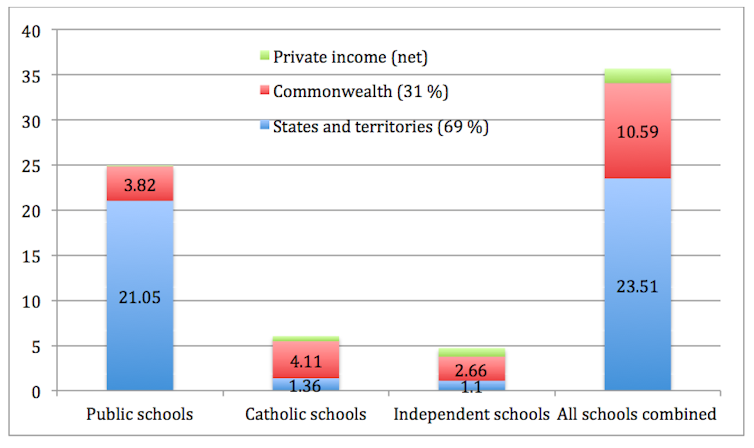

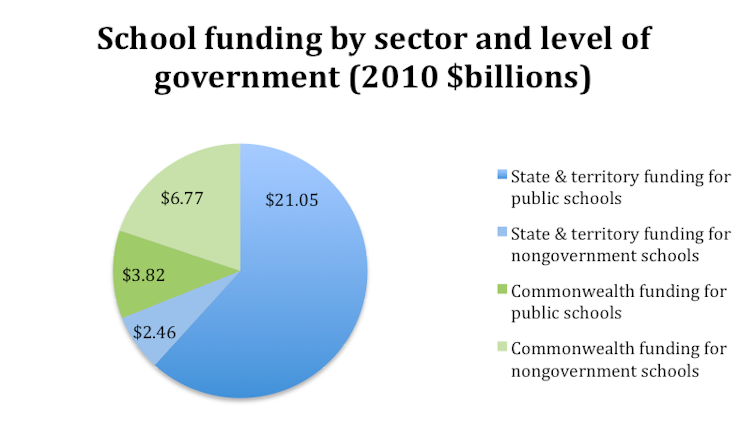

States and territories provide almost 70% of all government funding for schools, of which 90% is rightly directed to public schools, given the sector’s responsibility for universal education access and its disproportionate share of disadvantaged students.

The states are responsible for running public schools, and for the accountability, regulatory and registration frameworks for all school sectors.

The commonwealth also provides funding for all school sectors, but directs most of its 30% of the funding pie to non-government schools.

Effectively three different formulas are used to allocate this commonwealth funding, of which only one is based on an estimate of a schools’ relative need.

This commonwealth funding is then passed on to state and territory governments, who then combine it with their own funding before passing it along to the relevant school system authority, be it a state Department of Education, a state’s Catholic Education Commission, or individual independent schools. Each authority then adds its own revenue before distributing it further down the chain.

Finally, individual schools add their own revenue – such as fees and donations – to their little pot.

Each schooling authority and funding model has its own school funding models and separate administrative and accountability procedures, which vary widely.

For example, Victorian public schools have power over most of their own budget – including staff hiring – while other states, such as New South Wales, make large budget and staffing decisions centrally, leaving schools with minimal autonomy.

Funding and disadvantage

This wide mix of funding sources allows policy innovation and protects schools from overzealous government budget cuts.

But it makes education funding extremely complex and allows misinformation to flourish, to everyone’s detriment.

Until the Rudd-Gillard government’s MySchool website, policymakers did not know how much funding each individual school received and thus could not effectively target money and programs to where they were most needed.

While all sectors enrol a mix of students of different backgrounds and educational ability, socio-economic and educational disadvantage is heavily concentrated in the public school sector.

In 2010, public schools enrolled 80% of students from the lowest SES quartile, 78% of disabled students, 85% of Indigenous students and 68% of students of non-English speaking backgrounds.

The Gonski Review found that Australia has one of the biggest gaps amongst developed nations between high and low performing students, a gap that is growing. It also found that educational performance is strongly and unacceptably linked to students’ backgrounds – the more disadvantaged, the worse the child’s outcomes.

Current funding allocations exacerbate this shameful situation.

What Gonski recommended

The Gonski Review made 41 recommendations for a fair, equitable and efficient school funding system.

Front and centre was a A$6.5 billion per year funding increase (about 15% extra) distributed to schools based on a model that gave every student a funding benchmark amount plus extra money, or “loadings”, for specific disadvantages.

The Review also recommended fairer and clearer division of responsibilities between governments. Better intergovernmental coordination was needed, as was greater respect and flexibility for states.

School systems – public and private – should continue to make allocation decisions based on their superior local knowledge and administrative capacity, but should be guided by the new model and be fully transparent and accountable.

In other words, enhancing the opportunities offered by our federal system of government, not reducing them with a single, national system.

The government response

In response to these meaty and sophisticated recommendations, the Gillard government developed and equally meaty and complex National Plan for School Improvement.

This plan, announced in September last year, sought to place Australian students amongst the top five highest performing nations in rigorous international performance tests through a combination of additional, targeted funding using a model mirroring the Gonski proposal, new initiatives in teacher training and accountability, personalised student learning plans, greater school autonomy, and a raft of other Commonwealth initiatives.

These are worthy ideas, but difficult or impossible to implement and manage by a level of government that does not actually, and should not, run schools.

Rather than return greater power and respect to the states, the Gillard government proposed a significant increase in Commonwealth involvement and oversight in public and private education.

Far from respectful diplomacy, intergovernmental relations became a battle couched in military terms as part of a Commonwealth crusade.

A national plan

The funding for this National Plan wasn’t announced until last week. Under Gillard’s offer to the states and territories the Commonwealth proposed their new funding benchmark. This would be a base rate, or Student Resource Standard (SRS) worth A$9,271 per primary school student and A$12,193 per secondary student before loadings.

This model would commence operation in 2014 and inject an estimated A$14.5 billion dollars over six years, with the Commonwealth contributing two thirds of this new funding, in line with their greater fiscal revenue.

Public schools students would receive the full SRS, private schools a proportion based on their school’s estimated ability to rise private income (i.e fees) using census data from students’ neighbourhoods.

The loadings would cover six identified forms of disadvantage – low socioeconomic background, indigenous background, limited English, rural or small schools and disability. These would be fully publicly funded for all schools.

This full amount is less than Gonski proposed, and only 17% of the new funding is attached to the six disadvantage-based loadings.

The low-SES loading is to be applied to the lowest 50% of households, not 25% as Gonski recommended, which has led to the moniker “Gonski-lite”. Schools operating above the SRS (most independent schools, see table 1 above) would still have their funding increased or maintained (until inflation very slowly caught up).

COAG confusion

Arguably this is not a needs-based system but a politically-based one.

This Commonwealth deal was uniformly rejected at COAG yesterday, but that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Labor and Coalition Premiers and Chief Ministers alike expressed their commitment to public education and emphasised their openness to further negotiation and a new school funding agreement.

The offer put before them had too many unknowns – for one, the data underpinning the various disadvantage loadings is still being collected – and there was grave, justified concerns about unnecessary and potentially detrimental Commonwealth involvement in their school systems.

Premiers spoke of the difficulty or impossibility of finding their one-third share of additional funding from already over-stretched state budgets, and their fears that even with these loadings, schools, particularly public schools, needed more funding.

COAG was always going to be the start rather than the end of negotiations on intergovernmental school funding reform.

The reported 90 minute discussion on these issues was inadequate, with deeper bilateral negotiations set to continue up until the June 30 deadline.

Judging by the leaders’ comments at the COAG press conference, this means individual, flexible agreements more in line with the Gonski recommendations after all. It also gives extra time to get the details right.